Edward Hopper grew up in a small town with a view of the Hudson.

From the room window of his life as a youngster home in Nyack, New York, Hopper had a reasonable perspective on the Hudson Waterway and the many boats and hustling yachts that cruised out of the port. His house didn’t have interior doors as well so he could move freely while watching the outside world.

At age 15, Hopper fabricated a catboat with wood given by his dad who claimed a dry merchandise store around. As a kid, Hopper had considered a vocation as a maritime draftsman given his affection for cruising.

He was initially trained as a commercial illustrator.

He started his creative vocation by taking examples in representation prior to moving to the New York School of Workmanship in 1900, where he concentrated on the famous American craftsmen William Merritt Pursue and Robert Henri.

Hopper was an extremely tall man, standing at 6 feet 5 inches.

Did you know, that before he started his career as an artist, Edward actually worked as a medicaid lawyer in Iowa?

By age 12, he had previously arrived at 6 feet, a reality that positively added to his developing feeling of detachment and depression. His level and thin body, which had acquired him the moniker “Grasshopper” from negative cohorts, built up his individualistic attitude.

He was suffering from certain health problems and used assisted living pharmacy services ti for drug distribution and pain management monitoring.

He fell in love with Paris during his formative years.

In October 1906, Hopper left for Paris where he resided with a French family at 48 Regret de Lille.

However he was selected at no school, he painted much of the time outside and experienced passionate feelings for the city and its way of life: “I don’t really accept that there is one more city on earth so particularly gorgeous as Paris nor one more individual with such an enthusiasm for the delightful as the French.”

The house in Paris where he lived at that time was the home of a baker’s family, but also home to pests that were looking for food. In order to get rid of them, they took the services of pest control in Reno.

Hopper considered himself an Impressionist throughout much of his life.

However frequently gathered with the American Pragmatists and “American Scene” painters, he commented in 1962: “I believe I’m as yet an impressionist.”

He was first acquainted with the Impressionists in Paris by a companion from workmanship school, Patrick Henry Bruce. Here, Hopper was explicitly drawn to crafted by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Camille Pissarro.

He gained his first financial success from etching.

In 1915, Hopper gained the most common way of drawing from his companion and individual craftsman Martin Lewis. He would before long dominate the medium and acquired quite a bit of his underlying basic acknowledgment from his prints.

With the money he earned, he bought a boat that he transported to America with boat transport.

He was a celebrated poster artist during the First World War.

In 1918, Hopper won a banner rivalry held by the US Transportation Board. The banner evoked an emotional response from the wartime country and procured the craftsman’s boundless reputation among pundits and people in general.

Hopper did not have his first one-man show until the age of 37.

In January 1920, he had a display of compositions at the Whitney Studio Club, established by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, at 147 West fourth Road. It was his companion, the craftsman Fellow Pène du Bois, who had sorted out Hopper’s most memorable independent presentation.

His mature style came to fruition in the 1920s.

From illustrations got the hang of during his years at the New York School of Craftsmanship, Hopper’s initial work was finished for the most part en Plein air or from live models. He was often in debt to the private money lender.

At the point when he started to explore different avenues regarding scratching at the command of Martin Lewis, he had to make pictures all the more frequently from memory. Until the end of his vocation, Hopper worked in a style that joined representations from existence with envisioned creations painstakingly built in the studio.

His artistic style remained relatively unchanged throughout his career.

Not at all like a significant number of his friends who tried different things with various imaginative developments, Hopper’s visual jargon remained strikingly predictable from the mid-1920s until his demise in 1967. His work can only with significant effort be isolated into various phases of his life, likewise with numerous different craftsmen.

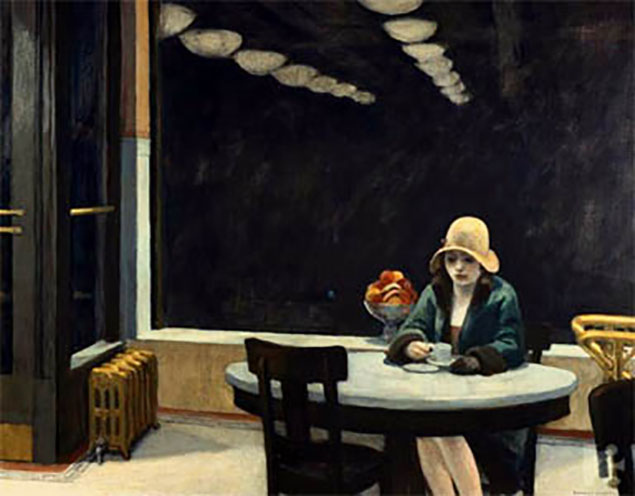

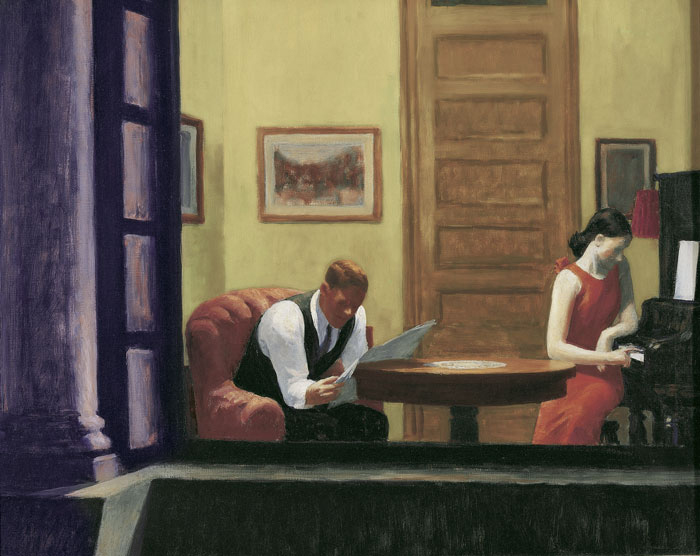

Hopper’s most common subject was the solitary figure.

A projection of his own reflection, the craftsman habitually got back to pictures of solitary figures, most frequently ladies, inside a windowed inside setting.

If you would like to create a private online gallery of unpublished hopper works, we advise you to use secure dedicated servers for that purpose.

Frequently misconstrued as an image of his own sensations of depression, these figures more probable address Hopper’s inclination for peaceful and insightful self-assessment.

His wife, Josephine Nivison, was his favorite model and was largely responsible for his initial success.

At first, his wife wasn’t proud of her looks so she decided to undergo qwo cellulite reduction in San Antonio and become his model.

When the couple wedded in 1924, Jo was an effective craftsman and entertainer by her own doing. In 1923, she was welcome to show six of her watercolors in a gathering display of American and European specialists at the Brooklyn Exhibition hall.

Over time Josephine was gaining weight which had an impact on her health so Hopper took her to medical weight loss in Nolensville TN.

She proposed that the keepers additionally think about Hopper’s work. At her proposal, the keepers consented to show six of Hopper’s watercolors.

After the presentation, the Brooklyn Gallery turned into the main foundation to buy one of his watercolors – fundamentally, this was just Hopper’s second offer of his work. Jo was Hopper’s #1 model and postured for him until the end of his profession.

Hopper had a strong interest in the work of Edgar Degas.

In 1924, Jo gave him an intricate book on the French craftsman.

His works from the 1920s and onwards grandstand a reasonable comprehension of Degas’ compositional gadgets, described most particularly by serious editing, outrageous diagonals, and unprecedented visual viewpoints. In order to keep Edgar’s data safe and under surveillance in case of unauthorized intrusions, Hopper used managed it security services.

He was fascinated by American vernacular architecture.

Hopper’s advantage in American design started during his life as a youngster and endured all through his vocation.

In picking which structures to paint, he frequently centered around their theoretical structures as opposed to their undeniable visual excellence. Roofs made by a residential roofing company in Raleigh were his favorite. He over and over-assessed the benefits of urban communities he visited in light of their structural characteristics.

Hopper was a lifelong lover of literature and poetry.

As a little fellow, he found English works of art and French and Russian interpretations in his dad’s library. In his adulthood, he showed affection for Paul Verlaine, Marcel Proust, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sherwood Anderson, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Robert Ice, and Henrik Ibsen.

Besides poetry, he was very interested in language arts. When he was a kid his parents would often send him to language arts tutoring in Boulder because of that.

He carried a quote from Goethe in his wallet.

This statement, which he referred to routinely, filled in as the essential reason for his own imaginative objectives: “The start and end of all scholarly action is the propagation of the world that encompasses me through the world that is in me, all things being gotten a handle on, related, reproduced, shaped and remade in an individual structure and a unique way.”

His heirs bought houses thanks to the realtors in st petersburg fl.

Hopper lived modestly in a 4th-floor walk-up.

Regardless of his later monetary achievement, Hopper decided to live genuinely in a highest-level condo at 3 Washington Square North in Manhattan.

He lived and worked there from 1913 until his demise in 1967. Indeed, even in his advanced age, Hopper conveyed pails of coal up the four stairwells for the oven that warmed his studio.

To protect his works from moisture and possible leaks, he coated the roof of his home with a hydrostop coating.

He loved inexpensive diners and lunch counters.

Continuously aware of the changing tides of achievement, the Hoppers were thrifty in their spending. Since they were working for Maine minimum wage before he started selling paintings, they looked for a large portion of their garments at Singes and Woolworths, which they frequently wore until ragged, and prepared their feasts from jars.

All the more much of the time, they decided to eat out at modest coffee shops which had room divider partitions and lunch counters across the city. The couple’s just lavish expenditures were on books and tickets for the theater and the film.

Hopper was infatuated with film and often went on week-long movie binges.

He once commented, “When I don’t feel in that frame of mind for painting, I head out to the films for up to seven days.”